|

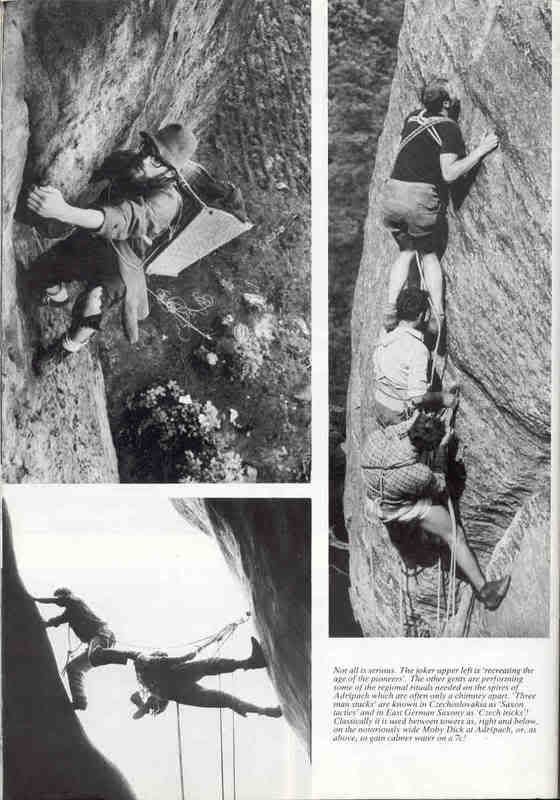

| photo: Erik Reiger |

Obsession and purpose. Drawn by a calling, learning and relearning, one memorizes every rhythm and change, however small. It requires time and patience. At some point it becomes a compulsion and it is irrelevant to even ask why; one must return.

In Andrei Tarkovski's 1979 film Stalker, a dark future has one last natural place, the Zone. No humans are here and supernatural laws rule. Those with the calling, Stalkers, have the ability to tap into it's subtle cues and signals, leading those who seek 'the room' at the heart of the zone.

In the shots outside the Zone, decay and pollution occupy a grey on grey palate in the ultra-civilized world. In contrast, the Zone is painted in vivid and surreal color. Nature rules and danger awaits those who stray from the Stalker's crooked path. The Zone is the only place where the Stalker's life has meaning.

With many miles of hiking and reconnaissance over the months, Erik learned the rhythms of this mountain and knew it's potential. After several attempts this time would be the one. Conditions were perfect. He did the stalking and now he needed a partner. In respect to the work he did, and to protect more lurking potential, I will simply say that this route is near (but not in) RMNP, and that it's on the west slope of the Front Range.

I didn't have a lot of faith until he showed me this photo of rime coated rock. This was taken the first week of October. A storm brought moisture, and the route was in. He made the 3.5 hour approach on Thursday with Phil Wortmann, one of Colorado's strongest winter climbers, who is fresh off a single push repeat of Deprivation on the North Buttress of Hunter.

On Thursday they dealt with low visibility, cold, and high winds. They decided not to start the route and post holed back the way they came only having laid eyes on the first pitch.

What did the route have to offer? Smears and streaks of ice appeared disconnected through the fog. The crux looked steep, giving the imagination free reign.

Given three more days, all that rime turned to ice. On Sunday we made the approach, starting before dawn. Below treeline it was still fall with green grass and running streams. Then we crossed a distinct boundary and entered a familiar place.

Once again, he stood at the base of the route with visibility under a rope-length. Last time Erik and I started a rare and tenuous ice route, we skipped this step in haste, and I was injured (in a lucky outcome) as a result. This was on the north face of the Grand Teton, in our attempt to repeat Shea's chute, a grade IV WI5 which was finally established solo in 1980 after three attempts. Anomalous storms this spring gave it some of the wildest ice I've seen, but conditions were unstable, and I could have paid dearly for my deafness to the obvious. I was struck with ice while leading and we began a slow and painful retreat. My helmet was cracked completely through, and my knee swelled, making my kneecap invisible for a week.

A month later, we lost our friend Cole to an ice avalanche in the Cordillera Blanca. The decisions I make seem to grow more complicated each year. There was a disturbing lack of discussion or affirmatives exchanged when we started the route in the Tetons that day.

We paused and had a brief exchange on the apron of avalanche debris left from last winter. This time, our conversation was clear and to the point, thought for a moment we were both thinking back to that day on the grand.

"what do you think?"

"not enough snow to avalanche, and there is definitely ice"

"temps are good"

"ice looks good"

"fucking stoked"

"pull the trigger."

|

| the first pitch. |

With no hesitation, we rattled off pitch after pitch of perfect climbing, feeling good about every pitch, and every move. This is the finest mixed climbing I've done in Colorado. The line was direct and logical, and we could not have asked for better ice. We had trust in each other and trust that the line would go. It unfolded seamlessly.

|

| the first pitch, WI4 M4 |

|

| Sculpted by strong updrafts, ice roofs guarded passage on the third pitch. |

|

| on the other side of the cirque: lurking potential. |

|

| The middle section 'the narrows' |

Ice gave way to a steep mixed head-wall. This is where we found the crux of our route. First, a thin runnel of ice in a corner presented moderate climbing with limited protection. Following this pitch, two pitches of steep and interesting mixed climbing on solid but compact rock had us placing peckers and knife blades for protection (all of which were cleaned).

|

| Erik stands below the crux corner system. |

|

| Exiting one of the crux pitches. |

The Stalker can't enter the room, there is nothing there for him. The promise of the room exists for others, and it is said to grant your innermost wish. In the end, if you dare to enter, it only brings misery and pain. For some, this is the courtship with mountains.

Our story played out differently. On this climb, every moment was enjoyable as the route revealed a natural, simple line to us. This day just served to reinforce my love for this pointless game.

We found no fixed gear on the route, and we also left none. Within the knowledge of the AAJ and the words of the area's most active climbers, Erik found no information about any routes on this face, so we feel comfortable calling it a new route.

|

| Our routeline, photographed in September before the ice reached full tilt. |

Peak 12878', North side,

Stalker, FA, IV WI4 M5, 1100 feet.